zachary of nine columbines

overview

evil evil evil evil evil EVIL EVERYTHING INSIDE HIM IS EVIL PRAISE THE LORD FOR REINING HIM IN. ZACHARY IS a good boy he listens to bird-stories to be like Camille and sometimes when he is being like Camille he can be like people. People are very nice to Zachary like in the hospital and the seminary, they help him not be sick and give poppies. Zachary is very sick he lives in the hospital. When he goes, outside of, asylum, walls, people at shops still nice to him too. Zachary will be like people and be nice to people.

World is lovely and beautiful! Lots of wonderful things, many people! Handicraft Architect Dei cannot be bad-mean just for no reason hurt Zachary. There is big reason but why? Bishops say that Zachary maybe is just very bad. High truth potential. Please beg for providence this is not it Lord. Zachary weird place if true. Bishops want him as medium but if he is very bad this should not be? If very bad he take over. Reject.

Zachary go outside touch soil. He is so healthy now! Hallelu! Find good soil for Camille. Tell His stories, do His stories, maybe make story (so much ego). Meet heretics and talk about things. Many things but Camille still the best please.

Camille bright and shiny. He is biggest and strongest and prettiest and good with warm peace-bells and best friend on the phone. He is strong enough to crush Zachary. Thing is highly praiseworthy. Stupid-edict does not crush Zachary. Rape you and take you in chunks stupid trash. (On the first day on the face of the deep a divide came to the waters—)

Many knives. No bloody.

Good job Zachary! Hallelujah, Camille! All good patience, it was for him.

story

The stars were not aligned when Zachary was born. With no poetry and no exaggeration, the night of his birth simply doomed him.

Welled in the points of every constellation, cosmic forces radiate their energies upon the earth. For newborns caught in their beams, their blessings stick to the soul for a lifetime. By the ram, initiative. By the scorpion, secrecy. By the scales, equanimity. By the goat, independence. None more venerate these astrological principles than the shamanistic tribes of Palida, who see in them not any pulp esotericism, but a reliable cypher to the mechanics of creation.

Outsiders dismiss it as poppycock. But if you want the truth?

They should not.

One day a chief, accomplished and well-esteemed, warily consulted his shamans for advice on how to conceive his firstborn. This would be a very eminent child, he insisted, whose bloodline traced over a thousand years back to princes from the Demiurge’s Glen. Generation upon generation of good marriage and good achievement had further compounded the bloodline’s power. Immense familial and tribal strength thus rested on this child’s excellence, and so, he wished to know, how might he create a child most excellent?

The shamans inspected the dates, inspected the charts, and scrutinised the chief’s suitors. They answered, at this date at this time, in this place to this woman, you will conceive an excellent son.

Grateful, the chief correctly courted the woman as told. Years later, on the correct date, at the correct time, at the correct place, they consummated to much celebration. Though secrecy protected the details, the tribe knew a prophecy empowered their son, blessed with many benefic qualities, and the prevailing energy of a Sagittarian sun.

Just over 8 months later he was born, premature.

Under the cursed sign of Ophiuchus.

It was the sign of liars, of killers, and defilers. The sign of witches and demons. The sign of the serpent, the eternal betrayer, Demiurge’s murderer, envious outsider, adversary of Man. Evil, evil, evil. No debate rose on what to do. Ancient protocol demanded the child promptly killed, lest his curse remain on the tribe, and lest he mature into a defiler as destined.

The embarrassed shamans couldn’t say how it happened. Everything they’d calculated had been perfect. Perfect place, time, date, wife, herself born under the perfect stars. Only their puzzlement eclipsed their disgrace. Meekly, after an excruciation, they offered just a simple reminder: that the mother in birthing him was doubly cursed, so to absolve herself, she must be the one to kill him.

She thought, Screw that! Come triple-curse me, you kiddie-cutter shitstains! That is my goddamn son!

She fled with him across borders to Kitiven, escaping to a rural town named Vamu. A tiny place, hosting little infrastructure but a mart, postie, and diner, Vamu’s dark history as the former haunt of the Archon tel-Sharvara repelled settlers, but attracted tourists. Where grain and eggs once fattened the coffers, now the cash flowed by the grace of the town’s curator.

He was a mild, respectable man. The little museum buzzed under his oversight, old structures and artifacts endured by his maintenance, and visitors returned not just to partake in more of his knowledge, but from simple enjoyment of charming impression he left of the town. “You can’t keep away, Mark! How’re you doing?” he’d laugh to returnees. Where to newcomers, it was, “Welcome to town, stranger. Mightn’t look it, but we got whatever thing you’re looking for — try me.” So he received Zachary’s mother. And indeed he claimed true. She wanted a job and a roof on the down-low. She got it, that very day.

He employed her as a maid to maintain the Sharvara house and allowed her to live in its attic. The work was simple, the money was decent, and the lodgings were fair. The house’s seclusion protected it from onlookers and all its amenities functioned. Then the curator supplied basics; groceries, clothes, a cot, a phone. Though he couldn’t promise he wouldn’t hand Zachary’s mother over if the authorities knocked, he would shelter them as best he could until that point. And, if it absolutely came to it, he would at least look after Zachary.

Zachary’s mother was a suspicious person. She disliked her dependence on the man and the ease of his charity. But she found little alternative. Months swelled into years under this arrangement, as she saved her paychecks and probed for connections to secure forged documents for Zachary. Then, she planned, she’d send him to the safety of a state boarding school or abbey, away from any notice or jurisdiction of the headhunters undoubtedly still stalking their asses. She’d secure herself and catch up with him later.

It took three years, but she saved the money and secured a good contact. She just needed to finalise the documents, drop off Zachary, and split. In and out. Thief in the night. Guy wouldn’t know she was going ‘til she was gone.

But Zachary was the right age now. And so.

Before anything else could happen, the curator reported Zachary’s mother to the authorities and stole Zachary away for himself.

Hell followed.

From ages three to six, Zachary was tortured nightly for the sadistic pleasure of the curator. His methods varied immensely, with no consistency or uniformity, but it was always horrible. He took special pleasure in finding new ways to inflict pain, and if you can imagine something, then yes, it was done or attempted.

Whenever he was absent, the curator kept Zachary bound in a rack in a drawer with a sack over his head and wire wound tight around his neck. Food came rarely and was never sanitary. Basic hygiene was not a thing. Zachary was too young to understand anything, but old enough to anticipate danger, curl up, and be terrified. It was constant pain and fear, day in, day out, and it never seemed to end.

The one exception, the one point of consistency, was the knives. Some fetish or obsession of the curator's led him to evenly slit lines upon lines of cuts on Zachary's skin, thirty minutes, always as the day’s final torture, the curator's ritual before he went to sleep. The regularity of it, contrasted to the randomness of everything else, comforted Zachary. He knew exactly what this entailed, how long it would go for, and that it meant hours would pass before anything else happened. It hurt. God it hurt. But at least he understood it. If there was anything that symbolised a reprieve, it was this. If there was ever anything to look forward to, it was this.

Early into the ordeal, within the first month, Zachary entered an Archon pact with Camellia. The dialogue went something like this: “AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA / omg what / MAKE IT STOP MAKE IT STOP MAKE IT STOP MAKE IT STOP / holy—hold on let me figure out how to nuke this guy / IT HURTS IT HURTS IT HURTS IT HURTS IT HURTS / wait no don't reach out to me it'll just make it worse / HELP ME HELP ME HELP ME HELP ME HELP ME, MOM? / oof" and poof Camellia disappeared before he could nuke anything. Zachary got his immortality, which saved his life and protected his body from dismemberment and total necrosis, but extended the torture far past the point where he should have died.

After three years, the curator finally tired of him. Though he’d long ago noticed Zachary’s resilience, he’d never before tried to earnestly kill him. But nothing worked. The nuance of the violence changed as the cutting ritual stopped. Zachary’s understanding of the world shook. Wracked with anxiety, he picked open his scars to comfort himself, and he envisioned something strange.

His fingers made him bleed the same way as a knife. It hurt the same way as a knife.

His fingers, his hands, were knives.

And they were still knives when the curator returned that night, yanked him out of the drawer, and move to shove him in a lockbox. He would simply bury Zachary somewhere secluded and that would be the end of it. But when the sack came off, and Zachary dragged his hand through the air, five gashes ripped down the curator’s chest. He collapsed, bleeding, and screaming, and screaming, and screaming. And screaming, and screaming, and screaming. And screaming and screaming and screaming and for some reason he wasn't stopping.

Zachary understood none of it. But once his fear of the screaming passed, he felt an odd sense of control that he couldn't exactly define. And it didn't feel bad. But the effort of exerting himself so much — malnourished, beaten, and in pain as he was — kept him from doing anything else or moving any further, as if he even wanted to.

They were discovered in the basement the next day when concerned locals went searching for the curator. Both were alive, despite everything, and both were forwarded to a hospital in the next town over. But Zachary’s wounds were vile. Such a rural hospital could never heal him, and at six years old, he was sent to Nine Columbines Sanitarium in Kitiven’s capital of Amsherrat.

Nine Columbines is the nation’s leading medical facility and rehabilitation centre. Originally an abbey commune, Nine Columbines is still run by clerics and maintains its strong religious ties. Though mostly known for its infirmary, it also runs a massive apothecary and cultivates acres of medicinal herbs. A substantial number of the staff live on the sprawling grounds, and facilities for them include greenhouses, libraries, and a parish. The last notable aspect of Nine Columbines is its asylum, dedicated to the care of long-term patients and the housing of individuals with special needs.

Zachary’s arrival frenzied the medics. Wounds this severe didn’t happen. People didn’t survive this, especially not kids. They hopped him up on all the sedatives they could afford, then got to work trying to fix the nightmare that was Zachary’s body.

Melted skin. Electricity burns. Infections that healed wrong, infections that still festered. Necrotized flesh, foreign objects, lacerations from head to toe. Severe emaciation and dehydration. Strange protrusions under his skin, boils, fever, disease. Acid burns down his oesophagus. Swelling. Parasites. Broken bones, bruised organs, layers of filth and bodily fluids soiling his skin and matted in his overgrown hair. There was no end to it.

While the medics operated on Zachary, a search for his family began. Though his ethnicity traced him to Palida, no legal documents arose for him. Anecdotes about the arrest of a Palidan woman in Vamu some years prior suggested him an illegal immigrant, but the woman’s trail before and after her deportation was stone cold. Officials soon abandoned the hunt, and ruled he would be kept as a ward of the church until he could be legally deemed independent.

Nurses moved Zachary into Camille’s old hospital room for intensive treatment. In Camille’s old room, under stained glass depicting religious symbols of Camille, with Camille’s arboretum hazy in the distance, and hopped up on a surfeit of drugs, Zachary one day succeeded in accidentally invoking Camille.

Bored and curious, Camille let Zachary project into his sanctum in the arboretum. Seeing that he was all of: a child, distressed, feral, alone, and an Archon to boot, Camille deemed Zachary his business and determined to help him. Camille’s company stimulated Zachary over his time spent bedridden, acclimatized him to positive interaction with other people, and got him over the worst of his “3 years developmental delay” hump. Undoing his trauma wouldn’t be that simple, but at least he wouldn’t be biting people or hiding under furniture or screeching for no reason at all (too often).

But more than companionship or safety, Camille gave Zachary words.

Rather, the semantic concepts contained in words. Such things, spoken by Camille, transmitted to the mind directly. The world, once an overpowering place, full of undefined things that existed and things that happened, began to take coherent shape. Actions had predictable consequences. Chairs were chairs. Windows were windows. Walls were walls. These things all had their purposes, and functioned in predictable ways. Somehow, the world was far less frightening now that he was beginning to understand it.

Their friendship proceeded heartily. Camille taught Zachary how to call him, taught him games, told him stories, and told him fables. Though Camille’s philosophical pondering dipped into territory untenable for most seven-year olds, the sheer psychic potency of Camille made Zachary understand the concepts anyway. In return, Zachary learned how to focus his thoughts to convey specific ideas and images, which Camille naturally heard. The developing rapport became normal for Zachary, and being that neither of them had anything to do except hang out, they hung out a lot.

With such frequent practice, Zachary could soon invoke Camille on command. No rituals, symbols, or incantations supplementing it. Just think about Camille, and — poof. There he was.

Nothing peculiar about it.

Initial treatment on Zachary’s wounds concluded after half a year. He still needed physical therapy to strengthen his limbs, and his coordination was horrendously poor, but at least he could leave the bed and venture around in a wheelchair. Therapists began focusing on his mental rehab and education — but winning his trust was difficult, and his progress was slow.

He was unruly. He was the kid who would knock stuff off your desk just to watch you pick it up. The stronger he got, the more he wandered into off-limits areas. He stole things and hid them, but returned them when asked — just stealing to prove he could. While on one hand it was amazing to see him express such confidence, on the other it was annoying.

Once he stole the head nurse’s keys to the medicine cabinet, his minders agreed: enough. Therapeutic as his explorations may be, at some point it did cross to negligence. To start, they held him strictly to curfew. And he utterly flipped out. Full on screeching, beating his head against walls, high-grade traumatic mental breakdown. The kid needed that sense of control, his minders conceded, and imposing obvious limits wasn’t going to work.

Scholastically, he was a mess. Some head trauma, or neural atrophy over a critical developmental period, had crippled him cognitively. He was 100% illiterate. Numbers past 10 defeated him. He had some listening comprehension, but it wasn’t very good. And to finish, he was mute.

It wasn’t that he refused to speak, that he was too anxious or shy. It was that he flatly just couldn’t. Ideas that ran so fluently in Camille’s company stuck in his head without reaching his throat. “I want this, I want that,” he would think, but the words to dress these concepts in spilled like mist between his fingers. And even then, the listening, too. Every phlemgy syllable out anyone’s mouth slapped into his ears as if coated in mud. Under that mud there gleamed meaning, he knew, and he caught those pinpricks readily. But trying to understand it was like trying to comprehend a foreign language purely from exposure, and his attempts at speaking ended at vague grunts or a stammer.

Seeing him struggle, the clerics began teaching him in herbs. Few normal subjects were feasible for him, and were he to have any marketable skills in the future, this one at least required no language. If he could click into making salves and poultices, growing useful herbs, and recognising valuable reagents, then he could have prospects as a botanist, or a gardener, or a pharmacist, or an apothecary. Something he could do at Nine Columbines. Since, sadly, realistically, he’d likely be staying here the rest of his life.

Time passed. Years progressed like this, things slowly getting into rhythm as Zachary started responding to therapy and acclimatized to the familiar presence of Nine Columbines’ staff and patients. He’d secured a shaky, but promising kind of stability, and the privileges that came with that.

Until he stole a knife from the kitchen.

It was shocking how natural it felt to have it. He was still so clumsy handling so many things, so what was with this one? Felt like it was part of him. Part of his hand. Or just, his hand.

The thought twigged the memory of the curator, screaming on the floor. Though he usually feared those memories, that one scene in particular never disturbed him. He wondered, how had that happened? Had he done that? Could he do it again?

His minder jogged over, panting, having chased him down across the whole wing. The atmosphere flipped the second he saw the knife. Though he asked for it back with all the calm he could manage, Zachary, for once, felt extremely reluctant to surrender this treasure. The minder abruptly asked Zachary how his tomatoes were growing — but Zachary recognised this trick, used too many times on other patients. The minder would engage him in conversation, lead him outside to the tomatoes, and while he was distracted, steal the knife.

For some reason that prospect was extremely threatening.

Zachary shook his head ‘no’. Usually his minders backed off when he did that. Not this time. But the more the minder tried the placate him, the more irritated he felt. And hadn’t this guy lowered his morphine dosage recently. He was always pushy about making him interact with other patients, too. Intimidated and justified, Zachary raked his hand through the air.

Gashes ripped across the minder’s body along the path of Zachary’s fingertips. He collapsed, bleeding, screaming, bloodcurdling, shrieking like a feral animal, seizing like a dying bug.

It felt good.

It felt like he’d communicated something extremely important. And he was the master of that thing. And it was powerful, and he was unstoppable. He was eleven years old.

But as he stood there watching, the minder’s screams resolved into something coherent:

Make it stop.

It hurts.

Help me.

Zachary trembled. His breathing hammered short and shallow; sweat dripped down his arms. Could he make it stop? It hurts? I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to. Me too, I hurt too, but someone did help me. Someone warm and bright — someone exactly like Camille. And so:

Camille, help me, please, help me, I’m scared, something’s wrong, I messed up, I don’t know what to do. And you know everything, you can deal with this, I can’t, you do it.

“Demanding, Zachary, but sensibly so,” said the most beautiful thing in the world, through Zachary’s mouth.

It was a strange sensation. The constellations above shone through the glass roof of the arboretum, and the mirrors lining the walls reflected the familiar sight of Camille. Here he was again, in his friend’s room and his own hideaway. But he vaguely sensed himself still in Nine Columbines, with his minder still shrieking on the floor, as he, Zachary, watched with an uncharacteristic air of authority and grace. And though dissociation was normal when visiting the arboretum, this time was distinctly off.

He had no time to think before it hit. A surge of fullness, tranquillity, rapture, reprieve. Recognisably, Camille’s soul. Though the soothing effect and hum of ambient bells was a constant phenomenon in Camille’s presence, Zachary had never felt it so potently before. A concord of carillons blasted away all doubt and fear and pain and hurt, and god, how the light cauterised him, exorcised everything dark and evil and ugly in him, drowning him to nothing beneath the blissful weight of—

—The hard stone floor of his room at Nine Columbines pressed painfully at his cheek. The chemical tang of hospital air burned at his nose. His clothes chafed against his skin. His wrists hurt, his leg hurt, his chest hurt, his neck hurt. All the usual aches and pains that came with being Zachary yanked him back into reality, ripping him away from nirvana.

Somehow, it seemed like it’d been over. And somehow, it seemed like that would’ve been okay.

Instead he was here, lying beside his wounded minder — still breathing, and quiet, now, but with eyes dead enough to belong to a corpse. Old wounds of Zachary’s had reopened, soaking him in blood. But worst of all was this feeling, this horrible intuition, that he had just transgressed far beyond his usual misbehaviour, and that, this time, he wasn’t getting away with it.

Nurses swooped in, drawn by Zachary’s bawling. They hospitalised him and his minder in the infirmary, and though Zachary recovered quickly, his minder never left that vegetative state. Unease spread among the staff as they struggled for some explanation — until a pilgrim, one of Camille’s elite agents, stopped by and promptly told them to drop it.

You don’t ask questions when a pilgrim says “drop it”.

Anxiety and curiosity still lingered, but that quelled the worst of it. News of the incident never left Nine Columbines, and most staff were faithful enough to feel reassured on the pilgrim’s word alone. Those unsatisfied with this resolution were without luck — the clues made no sense, and the only witness was young, dumb, incomprehensible Zachary.

Still. They couldn’t overlook this.

He needed absolute supervision. His petty misbehaviour crossed from ‘annoying but harmless’ to ‘dangerous’ with the theft of the knife. He was too skilled at sneaking away from his minders. He could navigate the grounds better than some younger acolytes or nurses, and for all his scholastic and social failings, he wasn’t so stupid or benign that you could talk past him, or ignore him, and expect him not to notice or capitalise on that. People who didn’t work with him often failed to anticipate his vague but present understanding of language. And he just caught people off-guard, constantly.

While the brass deliberated on what to do, Zachary had an important conversation with Camille. Which was the “hey you realise you’re not like, a normal person, right? You’re like, a magic person, and also dangerous” conversation, and also the “btw there’s this thing called heaven, nowadays it’s a euphemism for my awesome radical bastion of perfect euphoria soul, which is that thing that almost obliterated you into a realm of transcendent bliss yesterday, like how i obliterated your minder to deliver him from eternal suffering, except you’re too stuck in an archon pact for that to actually happen, lol” conversation. In short, Zachary was a monster barred from the gates of heaven. When the rapture finally, eventually came, and the world was made anew — he wouldn’t be let in.

It was a pretty heavy revelation. Though the exact implications eluded him, Zachary grasped this was horrible and terrible and really really bad. But before dread overwhelmed him, Camille intervened. Don’t misunderstand, it’s not incontrovertible. These pacts were something of a masturbatory sham, but they weren’t without loopholes. Camille would help Zachary find them, when he was ready, as he already was doing for others. As for the rapture, that was already on standby until Camille could resolve this and many other problems.

There was no need to worry, he emphasised. There was time. He wasn’t forsaken.

Camille wouldn’t abandon a friend like that.

If Camille had any immediate advice, it was to focus on his studies at Nine Columbines. To grow up a little. Have a life. And for god’s sake — don’t slice people up like that again. Camille could only weasel him out of so much trouble before someone puts two and two together.

Terrified, but reassured, Zachary listened.

Nine Columbines had decided. Zachary would come under the personal care of the facility’s pastor. While he’d remain on the grounds, and work with the same tutors, he’d no longer stay in the asylum. A stern but reasonable man, the pastor swore to find the line between over-permissive and overbearing that Zachary’s shifting and overworked minders failed to hit. Concerned voices protested, he’s a delicate child. Too much change or challenge stresses him into regressions. He needs constant treatment. He’s not well or stable enough. But the pastor kept firm.

The shift in environment indeed distressed Zachary. A new environment, a new face, and consistent new rules. Nothing about it was draconian — but neither was anything lenient, and finally, something challenged Zachary’s unchecked misbehaviour. A time out here. A gentle rebuke there. Though the pastor acknowledged and rewarded Zachary’s good behaviour, also, and was overall a good caretaker, his confidence crumbled. Suddenly, it didn’t feel like he owned Nine Columbines anymore.

He hated it.

He hated that this guy had kicked him off his throne. That he had to follow these stupid rules. That he couldn’t even argue back. That everyone around him was on edge. That he felt so sick and scared and achy and stupid all the time. That he was slipping, that he was back to feeling so anxious and jumpy. That he was snapping and lashing out worse than before, when he thought he'd gotten past this years ago. Come on. He'd been taught how to deal with this, he knew these people, they weren't dangerous, so why the hell couldn't he get a grip on himself? He couldn't even talk to Camille without getting pissed at him for no reason. His usual methods for cooling himself down weren't working, so he resorted to an old standby: picking open his wounds and ripping himself up.

Why did it have to feel so good, and so awful. You couldn't even tell which injuries were new.

If there was anything he did like, it was the pastor’s stories. They were clods of linguistic mud, but the challenge to his comprehension invigorated him enough, and he enjoyed the stories themselves if he filled in the blanks with his own nonsense narrative. But eventually one stuck out to him. As he wove his own interpretations into the narrative, he found himself perpetually recreating one of his favourite stories from Camille. And as he focused, more intently, on the pastor’s words, he found it was exactly that story.

Except the pastor was telling it all wrong.

Details were wrong. Events were backwards. Morals were misinterpreted. The tone was off. The rhythm, plodding. The delivery, so dry, so goddamn sombre. Camille’s version excelled it in every way. While Zachary’s muteness frustrated him enough normally, now, he bitchily confided to Camille, it just infuriated him that he couldn’t express how badly this stupid guy had mangled the story. Short of doing something bad and naughty, which would get him in trouble again, and chances were the pastor wouldn’t connect his discontent to the story anyway.

Camille contemplated. Indeed frustrating, he agreed. Why don’t you tell it to him how it’s meant to be told?

Was that a joke? He couldn’t, Zachary snapped. Or do you actually mean something by that?

I mean only what I say. Try it. You may be surprised, Camille urged.

Fine.

He pretended he was Camille. In his retelling he struck the same poses, held the same pauses, cracked the same grin, and indeed spoke the same words, so fluently he could’ve been doing it forever. The pastor, eyes bulging, trembled. So did Zachary.

Of course Camille was right. Camille was always right. He never should have doubted. But how?

Well, he reasoned to himself, these were Camille’s words. Camille’s words were always good. It didn’t matter that Zachary was saying them. By virtue of being Camille’s, they came out smooth and good. Zachary marvelled at the sense it made.

But when the pastor referred him to speech therapists, insisting they try again with him, Zachary could mimic them too. So it wasn’t that Camille’s words were good, though they were. It was that Zachary’s words were bad. That’s why they stuck. They were bad. Like everything else, everyone else had normal words that just worked. Zachary would be dejected, if the therapy weren’t working.

Stuttering, clumsy, and proficient as a toddler, sure. But goddamn, he was speaking. He could communicate! Like a child playing with a toy, he’d repeat words and phrases incessantly to anyone around. His irritation disappeared completely. On days where his pain anchored him to bed, away from his greenhouse and herbs, he nonetheless persisted in the day’s language study. His tutors would beg him to rest. But he didn’t. He summoned them in. Crowed for it, laughing.

The pastor watched on, in contemplation, still trembling.

A new habit ingrained itself in the pastor. Every afternoon, now, he’d carry a fat clipboard to the Director’s Office of Nine Columbines, then return a half-hour later, empty-handed and pensive. Zachary pounced the second the pastor’s silhouette hit the doorframe. Stories, he demanded. Book. More. Stories.

So the pastor would fetch the same thick book, bound in white leather with pages lined in gold leaf, direct Zachary onto the couch and settle into his recliner, and read a story about Camille. All the pastor’s stories were about Camille. Because the pastor loved Camille.

In fact the whole of Nine Columbines’ staff loved Camille. They would gather to hear Camille stories and sing Camile songs and sometimes celebrate special Camille days, like Czjeir-Tjetskin, and Hakkabbas, and the week of Meshardamut. Which Zachary had always known the staff to do, but never in deference to Camille. It was something they called religion.

Well, Zachary loved Camille too, and religion was absolutely genius.

Zachary dove into religion with the fervour of a fangirl into fics of her ship. He devoured every snippet of apocrypha the pastor would feed him, recited verses — paragraphs — chapters at opportunities both appropriate and not, barraged Camille daily with a new strain of questions: “Did this happen? Did that happen?”. Camille would grin his audacious grin, or half-lid his eyes and nod sombrely, or wheeze as if punched in the gut. Ah, Zachary would conclude, so it is canon.

“Zachary you do unlace me. I am undone. I am mortified,” Camille squeaked into his hands. No Camille, you’re very cool!, Zachary corrected, But how come you made gully-fish so big? And a deep loud groan pealed again through the arboretum, tailed into a sigh, tailed into a, “You’re too perceptive. Yes, indeed, that was…” and like this Zachary’s brain amassed religious lore of the greatest depth and secrecy.

Then he’d return to Nine Columbines, chipper with thoughts of Camille. He socialised more, he relaxed more, he involved himself in community events. He hummed the parishioner’s songs, helped the curates with simple chores (they always seemed to like his company), and grew more edible plants so the cooks had more correctly-sanctified ingredients ready for the Hakkabbas. Then he shared all his leftover tomatoes, like how Camille shared his things.

It felt nice.

He sat on a bench over a small stream tinkling through the garden. The sky was blue, the grass green, the air sweet with honeysuckle.

He didn’t feel scared or angry about anything. Not any rules, not any people. The apothecaries had hired him. He had an allowance.

For once in his life, everything aside, things just felt… god. What was the word?

Comfortable.

One day at breakfast the pastor, eyes and smile warm, asked: Zachary, next fortnight on Hakkabbas, would you like to visit the city?

tbc.... sometime

personality

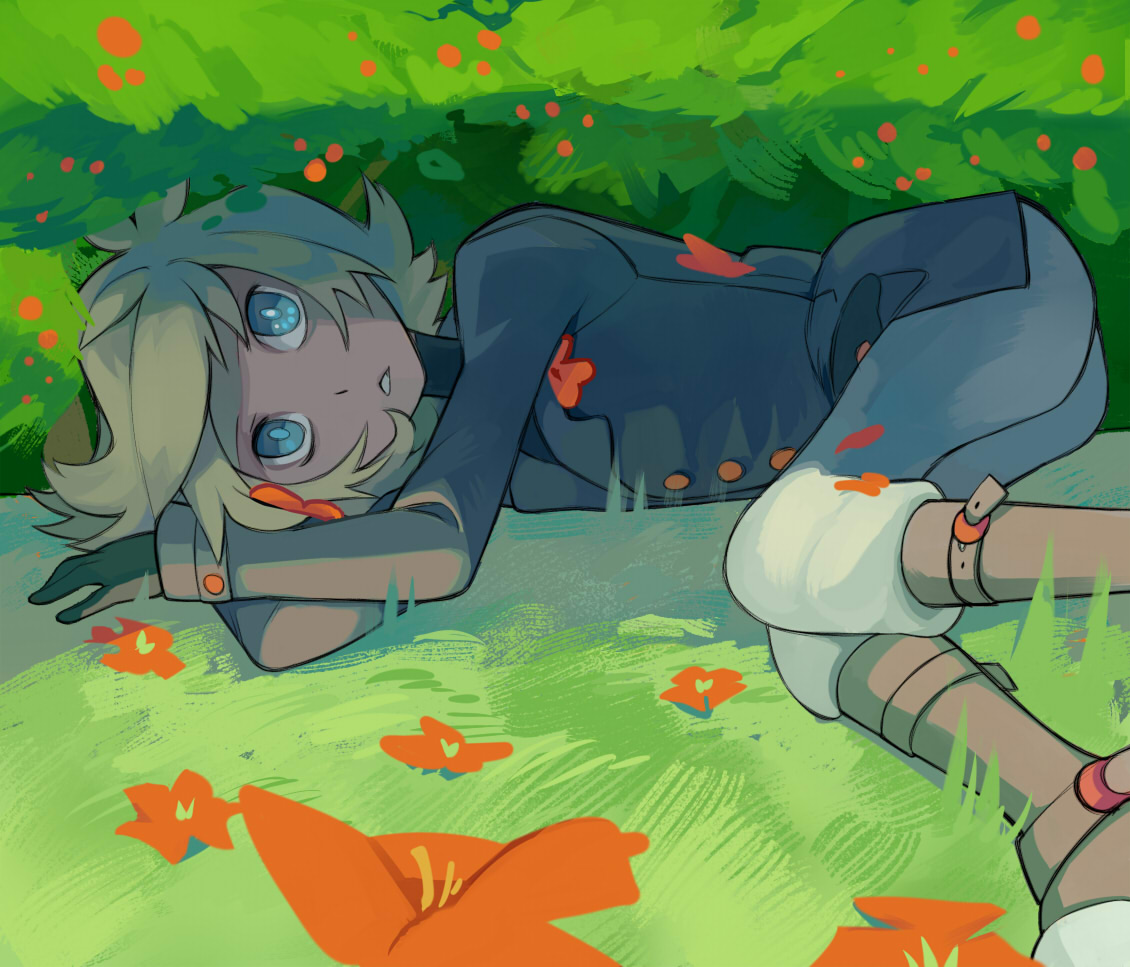

appearance

A moderately attractive boy with dirty blond hair and slate-blue eyes. Though his foreign heritage catches attention, in passing he is unremarkable and overall forgettable. Contrasting this, from the neck down, his body is horrifically scarred — melted skin, poorly-healed infections, slashes upon slashes upon slashes — all gruesome enough to provoke nightmares. As such, he keeps himself covered.

Wears a felt camellia on his left lapel, pinned over his heart.

personality

How beautiful this place, how wonderful its people, how thrilling their lives and how enriched mine is for attending! So Zachary could propound in a palace courtyard, in a tired suburb, or in a downtrodden slum with equal enthusiasm, powered by a lofty — and desperate — breed of optimism.

Abounding in resilience, Zachary has learned to see life’s positives and take things as they come. Small victories and self-forgiveness sustain him through day-to-day adversity, with earnest curiosity driving him to chase new perspectives and experiences. He feels himself developing constantly, and gleefully delights in all successes towards his ultimate goal of, perhaps, becoming a normal person.

That said, in Zachary’s mind, the benchmark for “normal” is literally Jesus.

Detail-oriented and poetically-minded, Zachary genuinely admires things most take for granted. Every blade of grass carries philosophical, moral, or religious implications to him, perpetually inspirational, but food for his neurotic zealotry. You can’t breathe around Zachary without him assessing the good or evil of it, nor stop him from recklessly intervening to champion goodness wherever it’s failing. Though his naivety can blind him to danger, and though he purposefully ignores troubles he can’t manipulate, once some incident engages him, he refuses to disengage until he’s won. Even when it’s none of his business.

Though, there’s an arrogance to Zachary, in that he takes everything as his business. While often doubting his praxes, he holds absolute conviction in the correctness of his principles, the adherence to which he believes indispensable for anybody’s spiritual maturation. Those who would seriously refuse them, he regards as either misguided, evil, or weak. Such people — those complacent to their vices, or who revel in their moral weakness — he holds in unsparing contempt, with especially cruel but quiet scorn towards those who self-harm or are suicidal.

Zachary, incidentally, has a history of self-harm and is deeply suicidal, though he rather fancies himself a providence-led martyr-to-be. Without the reassurance of a divine plan cushioning his missteps, Zachary fears himself too much to live. Impulsive, domineering, and plagued with dark fantasies, he feels himself perpetually balanced on a knife edge between ‘resembling human’ and ‘insane monster’. Though he bridles his demons quite confidently, the anxiety of a lapse tortures him. Preoccupations with self-control drive him to test himself constantly, a maladaptive habit that nonetheless soothes his ruminations and reactivates his optimism.

Socially, the kid is a trainwreck. For all his good intentions, empathy comes to him unnaturally and he’s often emotionally insensitive without realising. He bonds more from respect for people’s knowledge or experiences than from any particular liking of them, struggling to relate to foreign mindsets. Unrestrained, he naturally dominates others — conscious of this, he tries to humble himself and maintain his interpretation of contemplative open-mindedness and cordial formality. Still, anything that sounds like a challenge, he feels compelled to win.

Offer him an easy escape, and watch his disgust flip a mountain.

powers

ARCHON IMMORTALITY: MIRACULOUS SURVIVAL

Zachary cannot die. He inexplicably survives every injury that should be fatal. No wounds he sustains ever allow for dismemberment or debilitate him irreparably, though they can be very serious. He suffers pain normally and lacks any special regeneration or healing factor. Convenient coincidences and near misses otherwise abound around him, as if the world itself is conspiring to keep him alive and intact.

The guillotine’s blade jams in its frame, the fire fails to singe his organs, he gasps breath after hours on the noose. Try to atomize him with a laser, and… it just won’t. What a miracle.

ARCHON ABILITY: INCONSUMMATE HURTS

Pain inflicted by Zachary lasts until death. It never fades in fidelity, it persists even through the amputation or mending of an associated wound, and it resists numbing such as by medicine or restorative magic. Only death completely removes it.

Unintentional hurts inflict ordinary pain. If mild enough, like say from a light slap or pinprick, growing accustomed to it is feasible despite its permanence. If more severe, like from a stab wound, well. That could be a problem.

Intentional hurts inflict a supernaturally horrific, excruciating pain. The worst pain in existence actually. Bathing in bullet ants? Heavenly. Burning alive? Just a day in the sun. We’re talking an “AAAAAAAAAAAA INFINITY AAAAAAAAAAA OH GOD HELP ME AAAAAAAAAAAA PLEASE LET ME DIE SO I CAN RELAX IN HELL’S ETERNAL TORMENT AAAAAAAAAAAAAA” on the pain scale here.

So, like, let’s avoid that.

ARCHON ABILITY: ENDURING PRESENCE

Nothing can die around Zachary. As long as he remains present, everything around him stays alive through any fatal injury, illness, or condition. Unlike Zachary, though, those protected by this effect can suffer irreparable disfigurement or damage. They survive as a severed head, charred skeleton, or as atomized dust puddled around nerves and a brain. So, let’s hope nothing particularly grisly happens to anyone when Zachary’s around.

Zachary cannot inflict fatal wounds. Even wounds he makes that should be fatal, for whatever reason, just never are.

ARCHON ABILITY: GRAND SYLLOGISM

Zachary is a reality warper. By defining objects, ideas, and concepts in terms of A = B thus C or A =! B thus C, he can change their fundamental nature and their interactions with reality. He typically achieves this by metaphor, wordplay, and poetic interpretations of his environment, but it can also operate off of purely internal Zachary Logic.

Examples: Dipping his finger in a pool of water, feeling the wetness, and concluding the liquid is blood. Seeing a clear glass window, noting he can see though it, and concluding there is no glass. That kind of thing.

If a proposition makes no conceptual sense to him, rings untrue to him, or otherwise doesn’t ‘click’, Zachary can’t enforce it. Changes are also not literal unless he means it literally. If he deemed someone a dog for their loyalty, unless he literally meant he thinks they’re a furry four-legged animal, they will probably not literally turn into a dog so much as manifest traits characteristic of dogs, like urges to go on walks daily or a preoccupation with smells. Or whatever else specific of ‘dog’ Zachary meant at the time. Maybe he did mean they’re a literal dog to him. Who knows.

These alterations are always conscious decisions. No worries about power incontinence here, thank god.

INVOCATION: Camille

Zachary is a skilled invoker of Camille. He can telepathically communicate with Camille, project himself into Camille’s arboretum, and invoke Camille to possess him whenever. The “waaah, I give up, mooooooom heeelp meeee” manoeuvre.

PALIDAN HERITAGE

Zachary is ethnically Palidan. As such, he has some traits common to all Palidans.

• He has a tapetum lucedum, which gives him keen night vision. He navigates under starlight as if it were daytime.

• He has a nictitating membrane, which protects his eyes and increases their acuity underwater. It naturally closes if he’s underwater, but being raised in Kitiven, Zachary otherwise forgets he has it.

• And he has incredible lung capacity, being able to hold his breath for up to twenty minutes. Astounding.

relations

camille

anti-drug

Roles Camille fills for Zachary: God, sibling, best friend, teacher, therapist, confessor, father figure, mother figure, all-round role model. Damn Camille, you’re a strong little tree.

Zachary loves Camille and strives to be like Camille, as he thinks everyone sensible should. Camille is just the best in the world. Fact. Not opinion. No bias. Just truth. Don’t you want to be the best in the world? What are you? Weak? Look, it’s okay, it’s easy, he’ll show you.

Zachary credits his functionality to Camille. He dreads how he would’ve turned out without Camille, does not think he’d be Zachary without Camille, and in an allegorical way, attributes his birth to Camille.

Right now, things are a little shaky between them as Zachary questions the reliability of Camille the Archon against Camille the Demiurge. These are both Camille, so they’re both inherently reliable, of course, but…

It was easier when he didn’t have to think about these things.

swift

guide

Self-admitted witches’ familiar. Not a trustworthy entity. For that, though, Swift’s input as an on-the-ground voice of reason, wisdom, and worldliness has proven invaluably sound, so Zachary has come to respect him and his guidance on this pilgrimage. The depth of Swift's knowledge is stupendous, really.

He’s a touch too conservative, though, in that he sees problems with things like, strolling up to chemical waste pits that billow with noxious fumes, or speeding down winding cliffside roads at 130km/h. It’s not illegal, geez. Besides if they crash that’s providence anyway.

And, don’t tell anyone, but it’s nice to have serious, consistent philosophical discussions with someone who isn’t Camille, too.

Arsene

what?

Huh?

trivia

public perception

Nine Columbines liked him despite difficulties; local celebrity there with huge investment from staff. Nobody thought he’d reach his current functionality. Or survive.

Controversial among the upper clergy — a good kid, but questionable as Pontifex. Otherwise unknown to the public. His old tribe still wants him dead, but aren’t searching anymore.

in fights

Calls law enforcement. Otherwise, moves deftly for a minute then flags horribly. Takes outrageous risks and pushes himself to collapse. Quite able in that one minute where is he active though; mesmerising mastery of knifeplay and momentum. Ends knife fights bloodlessly, which is insane.

Knives love him and always end up with him. Wanna lose your knives? Show them Zachary. Swoon.

Refuses to inflict pain on his opponents or exploit Archon powers. Sometimes poisons with sedatives or narcotics. Physically weak but very persistent.

romance

Doesn’t do romance. Has zero clue what it entails. Not keen to learn, either.

hobbies

Exploration, travelling, stories, local mythology, moralistic pondering. Likes engaging with his environment through first-hand investigation — prone to wandering into questionable places if not careful.

Also enjoys wordplay and organic vocabulary study, often fixating on ‘fun’ words or phrases. Has an impressive if idiosyncratic vocabulary, despite his poor speech.

misc. trivia

- Full name is Zachary of Nine Columbines.

- Suffers from severe chronic pain, language deficits, and numbers deficits. Can’t read or write. Medicates his pain with strong opioids, obsessive prayer, and occasionally cutting, though he’s mostly phased out that last habit.

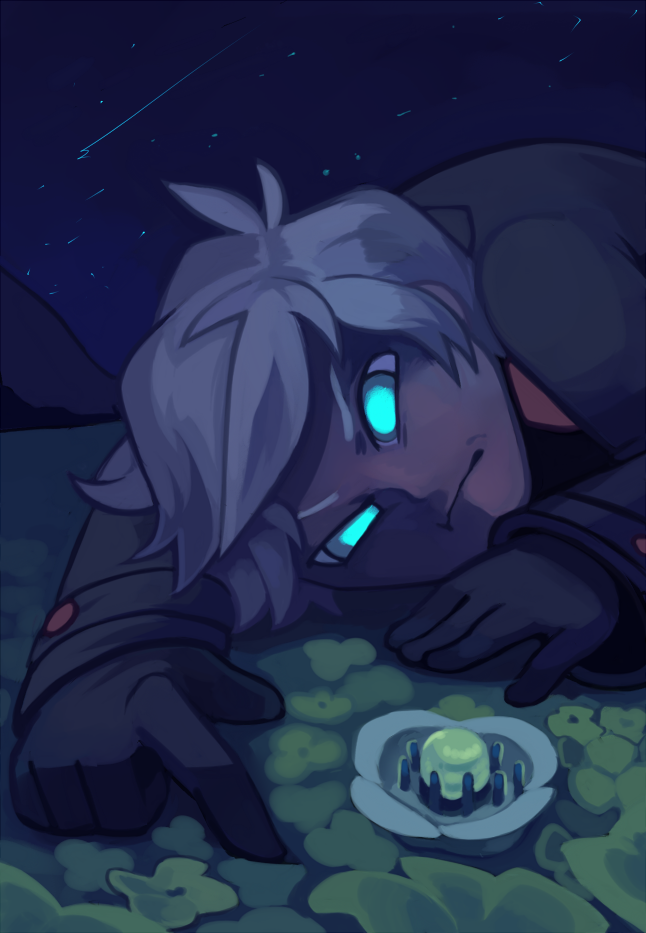

- Between constant pain and recurring nightmares, suffers from severe insomnia. Rarely sleeps so much as collapses. Sleep schedule is horrid.

- Skilled pharmacist, botanist, and gardener. Knows how to make a good variety of basic medications, aphrodisiacs, poisons, and narcotics from various plants. Funds himself by making and selling said medicines and aphrodisiacs.

- Fluent and comfortable when communicating with mind-readers and psychics. Extremely skilled at focusing his thoughts into precise ideas for them to read, though he isn't psychic himself.

- Abysmal with money. Impulse-buys a ton of stuff and is easily scammed — never knows how much or little he’s spending or should be spending, just guesses until people give him things.

- Has a stupid number of knives on him at all times. Not intentional it just happens.

- Hates children. Seriously uncomfortable around them.

- Loves ugly eye-bleeding uncoordinated outfits. Zero fashion sense, like, below zero fashion sense. Current presentability is a miracle.

- Favourite colour is chartreuse. Favourite treat is black licorice. Favourite drinks are cold black teas and kombucha.

- Abstains from alcohol. Would be an absinthe guy if he drank though.

meta/crack

gallery

art

writing

The Asp and The Hierophant

Dec 2018 | G | 1,862 words.

Characters: Zachary

Zachary yells at some bishops to GO TO BED so their accidental invocations can stop bothering him, then feels bad about it. Set a couple months before his pilgrimage, he's late 17~early 18 here.

For The Sallows

Dec 2018 | R-16 | 4,326 words.

Characters: Zachary | Camille

Warnings: Suicidal ideation, self harm, slur use, corpse defilement

Zachary has a difficult day and enjoys the freedom of Nine Columbines at night. Set a few years before his pilgrimage, he's maybe ~15 here.

zachary of nine columbines

more than the weekend